houseplants

I have 37 houseplants. I just counted.

I have 37 houseplants. I just counted.I don't think of myself as the houseplant type; the houseplant type is, by nature, a nester. I am not a nester. Never have been. We used to move every time the place we rented got too skanky. Now that we own, we share our house with dust bunnies of prehistoric dimensions and prehistoric temperments that are best thought of as the Deadhead roommates who never do the dishes. In fact, the floor is so filthy that we tell our guests to keep their shoes on so their socks won't get dirty (especially those yuppie guests who start to remove their shoes as a quid pro quo the minute they come in the door). I like to think that we're at squalor equilibrium: when you open the front door, about the same amount of dirt goes out as comes in. See what I mean? Not a nester.

But now there are these 37 houseplants that'd signal otherwise.

Where'd they come from? How is it that 5 orchids, 5 alocasias, and a tall spiky tree-like thing live in the bathroom, 9 of the plants occupying the tub itself? One alocasia has taken it upon itself to send a shoot into the sink at such an angle that one of the leaves invariably sends my contact lens case clattering to the floor whenever I wash my hands. But they grow well in the bathroom because it has a skylight, offering the finicky plant a perfect level of indirect light; I don't have the heart to put them anywhere else.

It wasn't sudden, this invasion. It was gradual, the way things are that creep up on you. First there's one; then several; then quite a few, but spread out so it doesn't seem like there are terribly many. Finally, the trend becomes undeniable. They're everywhere you look.

Twenty years ago I insisted that I didn't want houseplants. They'd all die if I went out to buy an LA Times and didn't come home for a few months. Too much trouble to have living things in my care. But when Tim moved to Colorado, I took in two of his plants, both philodendrons, the weed of the houseplant world, the kind you see everywhere -- in offices and dorm rooms; in restaurants, suburban family rooms, and studio apartment kitchens. Hearty suckers, those philodendrons. I still have Tim's philodendrons. The trouble with philodendrons is that they are way too easy to propagate. You put a cutting in a glass of water and -- poof -- another philodendron. Two becomes four becomes sixteen. And so on. It's a miracle that I don't have thousands of 'em.

Rescue's been a theme with these plants. One Friday in the late 80s, Pattie, Dan, and I were have drinks at some hokey Mexican restaurant in Palo Alto with Christmas cacti on the tables. Compadres. An overenthusiastic marguerita-inspired gesture sent just a few segments of Christmas cactus onto the table. I wrapped the segments in a napkin and brought them home. Big mistake. Turns out that's the way the little devils infiltrate your home and hearth. They break off the main plant and they root in the first cubic inch of soil they find. It's a big plant now, that Christmas cactus, and I have at least 4 others, if you don't count the ones that have found their way into the homes of friends and relatives. Others have fallen off a larger cactus and rooted in another plant's pot.

Take Harvey, for example. Harvey has a big pot that's just full of volunteer Christmas cactus plants. They fall off the Christmas cactus on a table and into Harvey's pot. That's all it takes.

Harvey is a ficus tree who I assume was named for Harvey Milk, a one-time resident of our fine neighborhood, an activist, a former member of the SF Board of Supes, and an all-around good guy, who was assassinated in his office at City Hall by Dan White, a crazy-assed twinkie-poisoned homophobe who was also on the Board. The assassination was tragic; I still weep when I see the documentary. Since then, many things around the neighborhood have been named after him. But Harvey the ficus is nothing like its namesake. What the tree does to distinguish itself from the other houseplants is that it behaves as if it were living outside. It's always losing leaves, but worse yet, it constantly issues these crazy brown berries. Plop. Plop. Plop. I can hear them falling onto the hardwood floor in the quiet of deep night. But they don't just fall; they fall and roll. Dozens and dozens of them. Every week is autumn in our living room as I sweep up piles of leaves and ficus berries. If you lift the cushions off the sofa, you'll find whole caches of them. Not coins; not cracker crumbs, but hundreds of ficus berries and dried leaves. Mark would like to take a miniature chain saw to Harvey, but you can't do in a plant named for a local hero. In fact, you can't do in a plant that has a name at all. Once you've named the pig, you aren't going to be eating bacon, right?

The palm trees also produce fruit, small bright yellow things that are the moral equivalent of dates, only so small that it'd take millions of them to make a fruitcake. And I don't know where you'd find those gross neon green candied cherries made to the same scale anyway. The palms are also refugees, a welcoming gesture when I returned to Xerox in 1996. Bobbi, Bob's indispensible secretary, had one of those florists' baskets of plants delivered to my office my first day back at work. They were originally planted in a disposable clear plastic container in damp mossy stuff; you could tell they were only meant to last a few weeks, just a little longer than cut flowers. They're supposed to only last as long as your optimism about the new job does; you and the plant basket are scheduled to wilt in harmony, when you both realize what you've gotten yourselves into. That you're in a low-light situation and it's not going to get much brighter. But somehow these palms are survivors. They've maintained their chlorophyll through four jobs, easily outlasting the other welcome swag like t-shirts and ergonomic chairs, and certain well outlasting my optimism and enthusiasm.

Then there are the orchids. Fussy epiphytes, these orchids. For plants that don't give a damn about soil and normal plant concerns, orchids require plenty of attention. You don't buy orchids for yourself; they're usually given to you and are extraordinarily effective at eliciting guilt because you're always in the process of killing them. Seemingly willfully so. From the moment they arrive in your house. They're in bloom when you receive them, and that'll be the last time you see flowers on them until you completely give up on the plants and put them in some obscure corner to die while you -- consumed by guilt -- tend to the philodendrons, which have meanwhile taken root in the carpeting.

I used to have an indoor bromeliad too, a lovely spiky thing that willfully drew blood during each week's arduous watering process, which somehow required a turkey baster as part of the ritual. But after moving it from room to room over the course of 17 years to find the ideal light level, I finally put it outside, where it seems to be doing quite well.

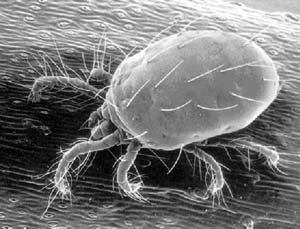

The other thing you've got to know about houseplants is that no matter how healthy they are today, a week from now they could have spider mites. Vibrant green leaves wither quickly and turn yellow; every surface becomes covered by a weird webby substance. And if you peer at the leaves long enough, you'll see legions of tiny bugs. I'm sure if you magnified them, they'd be so ugly that you'd have to give each one its own tiny spider mite makeover. Spider mites will cause even the most ardent environmentalist to go running for the insecticide. But what you soon find out is that the insecticide doesn't kill the spider mites, but rather kills the plant with the idea that the spider mites'll move on since they don't have anything to eat. But unlike houseplants, spider mites are wonderfully adaptable. The same spider mites that only a week earlier could eat nothing but alocasias quickly developed a taste for Boston Advance Contact Lens Conditioning Solution. And there's nothing grosser than a crust of spider mites mixed with polyvinyl alcohol, unless it's those green candied cherries.

The other thing you've got to know about houseplants is that no matter how healthy they are today, a week from now they could have spider mites. Vibrant green leaves wither quickly and turn yellow; every surface becomes covered by a weird webby substance. And if you peer at the leaves long enough, you'll see legions of tiny bugs. I'm sure if you magnified them, they'd be so ugly that you'd have to give each one its own tiny spider mite makeover. Spider mites will cause even the most ardent environmentalist to go running for the insecticide. But what you soon find out is that the insecticide doesn't kill the spider mites, but rather kills the plant with the idea that the spider mites'll move on since they don't have anything to eat. But unlike houseplants, spider mites are wonderfully adaptable. The same spider mites that only a week earlier could eat nothing but alocasias quickly developed a taste for Boston Advance Contact Lens Conditioning Solution. And there's nothing grosser than a crust of spider mites mixed with polyvinyl alcohol, unless it's those green candied cherries.If I were adaptable, I'd raise spider mites instead of houseplants.

1 Comments:

I googled "ficus berries" and came across your posting. I was searching for info as to when the beast of a ficus tree (over 50 years old) outside of my home would stop shedding its berries... wound up reading your posting and was thoroughly entertained with your plant story. You have a fantastic writing style... thanks for the laughs!

Post a Comment

<< Home